Bune: The 26th Spirit of the Ars Goetia

Origins in Demonological Texts

Bune, sometimes spelled Buné or Bimé, appears in several cornerstone works of Western demonology, including Johann Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (1577) and the Ars Goetia, the first book of the Lesser Key of Solomon (17th century).

Both grimoires catalogue infernal spirits and their offices, describing Bune as a Great Duke of Hell commanding thirty legions of subordinate spirits.

Weyer records that Bune grants wealth, wisdom, and eloquence to petitioners and can influence or communicate with the dead.

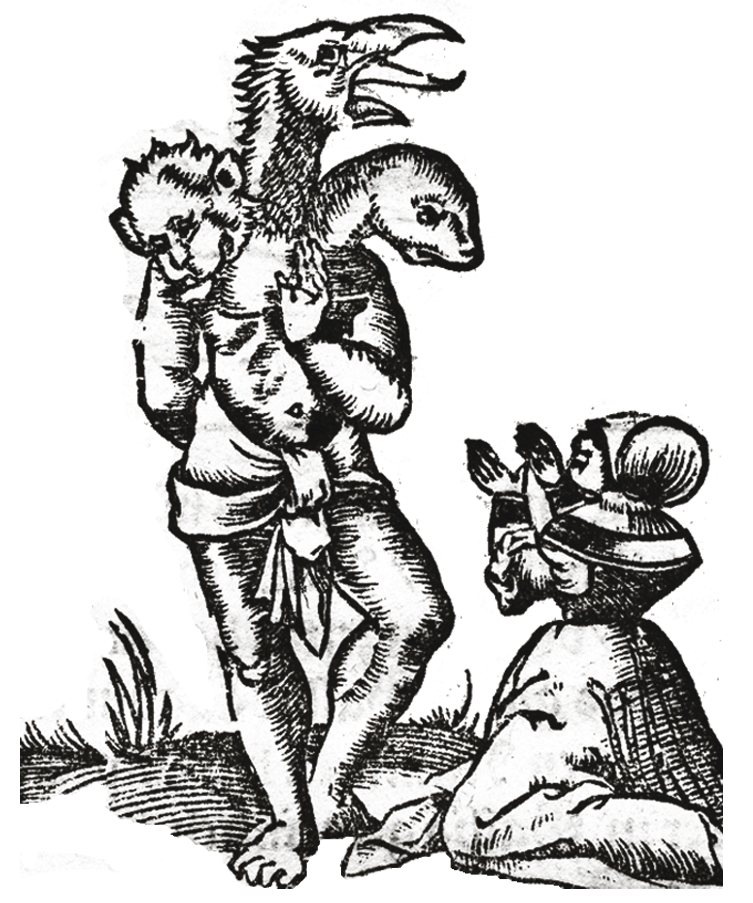

The Ars Goetia repeats these traits and adds his appearance as a dragon with three heads—one human, one canine, and one griffin.

This triune image reflects the layered symbolism typical of Renaissance occult writing.

Attributes and Powers

Bune’s primary associations concern material prosperity and intellectual mastery.

He is said to enrich those who call upon him and to sharpen their reasoning and speech.

Such gifts mirror the ambitions of early modern magicians, who viewed demonic intermediaries as sources of worldly advantage and rhetorical skill.

A second attribute is necromantic insight.

According to the Ars Goetia, Bune can compel the spirits of the departed to speak, granting access to secret knowledge.

This function situates him within a broader medieval belief that certain spirits could bridge the living and the dead, acting as interpreters between realms.

Symbolism and Representation

The Goetia’s vision of Bune as a three-headed dragon is rich in emblematic meaning.

Dragons traditionally symbolize power, guardianship, and transformation.

Each head expresses a facet of dominion:

- The dog’s head implies loyalty and protection.

- The griffin’s head evokes nobility and strength.

- The human head represents intellect and articulation.

Together they form a composite being embodying earthly, mythic, and rational qualities—a reflection of Bune’s command over both knowledge and material fortune.

His thirty legions mark him as influential yet approachable within the infernal hierarchy, a spirit of authority rather than absolute rule.

Role in Ritual Literature

Within the Lesser Key of Solomon, Bune is one of seventy-two named spirits, each linked to a unique sigil.

Ceremonial magicians of the Renaissance were instructed to employ these seals within controlled spaces such as protective circles.

The texts emphasize deference and precision, portraying demons not as objects of worship but as powerful intelligences bound by divine authority.

Practitioners viewed the interaction as contractual: a summons, a request, and a dismissal.

The elaborate precautions reveal the period’s conviction that such entities were dangerous if addressed without respect or theological safeguards.

Historical Context

Bune’s presence in both Weyer’s and the Goetia’s catalogues highlights the fusion of Christian theology, Jewish mysticism, and classical myth that shaped early demonology.

Composed during an era of theological conflict and scientific curiosity, these works turned the study of spirits into a taxonomy of metaphysical forces.

Bune’s roles—bestower of wealth, teacher of eloquence, and medium of the dead—mirror Renaissance ideals linking knowledge, speech, and divine order.

Weyer, though skeptical of witch trials, still preserved these descriptions as cultural evidence.

Later occultists inherited his framework, reinterpreting Bune as a spirit of intellect and transformation rather than pure malevolence.

Conclusion

In the Ars Goetia, Bune stands as a Great Duke of Hell who unites power, wisdom, and communication across worlds.

His tri-headed dragon form, his thirty legions, and his gifts of eloquence and wealth capture the Renaissance fascination with hidden hierarchies and forbidden knowledge.

Through Bune, readers glimpse a world where theology, philosophy, and magic converged—revealing humanity’s enduring desire to understand and command the unseen.